This blog was originally published on the UNDP Innovation account on Medium and posted on 26 July 2021, by Søren Vester Haldrup. Find the original blog here.

"Deep Demonstrations entail a new way of working and they often have a more transformational intent than traditional UNDP change projects"

Over the past year several UNDP country offices have engaged in efforts to better understand and tackle complex systemic challenges. They’ve done this through Deep Demonstrations and they’ve been supported by UNDP’s Strategic Innovation Unit (SIU) — the team I am part of. These Demonstrations have an inherently transformational intent: to change how we understand and engage with complex policy problems such as circular economy and the future of work. By questioning and changing the way we do things, we strive to engage our partners in a joint learning journey that we hope will trigger broader transformational change in the real world (read more about this here).

Each Deep Demonstration offers unique insights into the complex processes of change in an organization. As to be expected, change has not been homogenous across the board — its characteristics, dynamics, and pace have varied. This presents lessons for us.

This piece provides a tentative analysis of how we can help create the largest space for change in our Deep Demonstrations. It draws on insights from our first generation of Demonstrations and explains variation based on differing levels of authority, acceptance, and ability. It draws on the Triple-A framework for analyzing the space for change as developed by the Building State Capability programme at Harvard University.

From What I Planned vs What Happened

Change, complexity and the three A’s

It is difficult to make change happen or indeed to understand how it happens — whether it is inside UNDP or some other complex system. In his excellent book How Change Happens, Duncan Green explains:

“in complex systems, change results from the interplay of many diverse and apparently unrelated factors… because of the sheer number of relationships and feedback loops among their many elements, they cannot be reduced to simple chains of cause and effect.”

Due to this complexity, the pathways of change in any particular context will vary. A UNDP country office, for instance, presents its own unique setting with a particular operating context (say in Palestine or Ghana) and an office with an eclectic mix of personalities, expertise, leadership, history, and organizational culture.

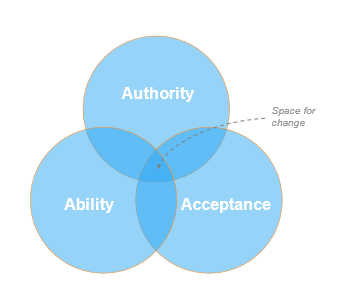

To help us learn more about how and why change happens in these types of contexts, I have used a simple analytical tool called the Triple-A framework. This heuristic points to three key factors influencing the space for change:

- Authority refers to the (political, legal, organizational, personal) support needed to effect change.

- Acceptance refers to the extent to which those who will be affected by change (in a UNDP office or in government) accept the need for change and its implications.

- Ability focuses on the practical side of change, such as the available skills, time, and funding to start a proposed intervention.

In essence, change is all the more likely to happen when these three factors coalesce (as in the visual below).

The Triple-A Framework

Using this framework, I’ve analyzed how authority, acceptance, and ability shape dynamics of change in our Deep Demonstrations. To do this analysis I have relied on a variety of data sources, including survey responses from Deep Demonstration teams and country office leadership, inputs from partners such as Snowcone & Haystack and Chora Foundation, and reflections shared by colleagues such as UNDP’s regional innovation advisors.

Authority

We have been fortunate that the Deep Demonstrations have (so far!) enjoyed a high level of authorization from senior leadership in UNDP — both at the country office, regional and headquarter levels.

However, as to be expected, the degree of authorization has varied from one context to another. Deep Demonstrations entail a new way of working and they often have a more transformational intent than traditional UNDP change projects. To date, we have seen different perspectives on what and how much the Demonstrations are expected to transform in a country office and, indeed, in UNDP as a whole. For instance, in some Demonstrations stakeholders have perceived the initiative as an opportunity to build completely new core capabilities and fundamentally change how teams collaborate, how the office engages with complex problems, and works with stakeholders. In these instances, the Demonstrations’ transformational intent has enjoyed a high-level of authorization. However, in other instances, the Demonstrations have been seen as a vehicle to gain new tools and ‘policy offers’ that fit within the existing way of doing things. In these cases, the Demonstrations have not enjoyed authorization for big transformation. In the SIU, we can get better at helping to foster clarity on the intent among all key stakeholders involved, to ensure that the right authorizing environment is in place.

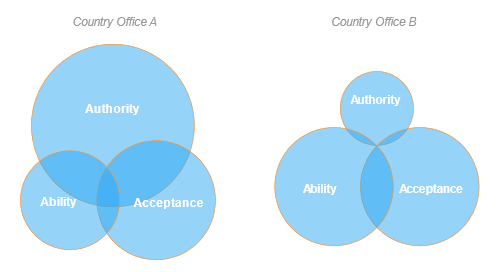

The visual below provides a generic illustration of how the space for change shifts with higher and lower degrees of authorization.

Varying space for change depending on the authorizing environment

The authorizing environment in the different Deep Demonstrations have influenced how teams work. Teams working in a context with a high level of authorization have felt they had the space and (small p) political support to work in new ways (e.g. to radically shift how the office approaches the future of work). However, in instances where we haven’t managed to nurture the right type of authorization, teams have lacked room for maneuver, which has limited the scope for change.

Authorization exists at multiple levels and it is not static. Authorization exists not just at global, regional, and country levels, but also within teams in a particular office. In the context of the latter, we have seen how important it is to have an energetic team leader who can maintain momentum in the group. At the SIU, we need to get better at effectively supporting these team leads. Authorization can also ebb and flow over time. Fortunately, over time the level of authorization tends to have increased as UNDP office leadership have been able to give teams space to pursue a more transformational intent.

Lessons learned about building authority: over the past year we have learned a few things about how to support a greater level of authorization for the Deep Demonstrations (and similar change initiatives). We are drawing on these insights as we roll out the next generation of Deep Demonstrations during the second half of this year. For the SIU, key lessons include:

- Invest more time in communicating and clarifying expectations in the Deep Demonstrations, ensuring that both leadership and technical level colleagues in country offices are comfortable and equipped to adopt a transformational intent, and that they feel they have the backing from key champions at UNDP globally.

- Dedicate sufficient time throughout the process to have one-on-one talks with country office leadership, to make sure they understand what they are walking into and that they have the requisite support to see it through.

- Invest greater energy in identifying and addressing pinpoints and incentive structures that may reduce or undermine the authority of key champions. This includes supporting champions (such as country office leadership) to navigate and manage these.

- Identify and nurture champions at country level among regular office staff and ensure that the Deep Demonstration team has a dedicated and forceful lead.

Acceptance

Acceptance is about the interests that different agents have in change. While authority primarily relates to key decision-makers and other authorizers, acceptance concerns a much broader group of stakeholders who have influence on an initiative.

Initially, the Deep Demonstrations have focused primarily on generating internal change in UNDP: equipping country offices with capabilities and mindsets to tackle complex challenges. In this connection it has been important to enjoy acceptance from the people working in these offices.

When it comes to acceptance in country offices, this in part relates to the teams working directly on the Deep Demonstrations. In this area we have seen a high level of support. These teams have a high degree of immediate influence on the Demonstration (they make or break it) and fortunately most team members have been very supportive of the work and felt they have learned new skills and that they see the world differently.

Acceptance in part also relates to wider support from the country office. Interview and survey data provide evidence of a good level of interest and buy-in from the wider country office. One of the positive drivers of buy-in has been the composition of Deep Demonstration teams as they have involved members from different thematic teams (such as governance, environment, and the Accelerator Labs). A member of one Demonstration team explained this: The team is cross-cluster, so it has a demonstration effect to the entire office of how interesting and innovative solutions we can come up with when we have multi-sectorial and multi-functional teams.

Yet, we can also improve how we empower teams to nurture acceptance and uptake of new ways of working in the wider office. On one occasion, a team member from one of the Demonstrations pointed to this noting: In my point of view, there have been changes in the core team. We seem speak the same language of systemic design and innovation facility. However, I don’t see significant changes in the wider Country Office.

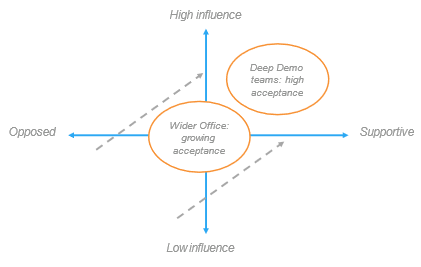

The visual below provides a simple representation of varying levels of acceptance among country office stakeholders and how this has improved over time (with a direction of travel towards the right-hand side of the diagram).

Varying levels of acceptance among country office stakeholders

Acceptance also concerns external stakeholders, which we are only beginning to tease out. For offices implementing Deep Demonstrations these include governments and funders. Acceptance at this level is still a work in progress, as our main focus to date has been internal. Yet, several offices have begun to engage and seek support from influential partners in government and donor agencies. Some offices have had success in securing acceptance at this level. For instance, in Colombia and Bolivia, the teams have engaged the Swedish development agency (SIDA) on new investments in the governance and regional development fields based on Deep Demonstration work.

Lessons learned about building acceptance: again, we have learned new things about how we can help ensure a greater level of acceptance for the Deep Demonstrations to support change. For the SIU, key lessons include:

- Devote greater focus earlier in the process on helping offices nurture and secure acceptance within the wider country office and among external stakeholders.

- Invest in more socialization and communication activities to generate early interest and buzz around the Demonstrations.

- Adjust workplans in Demonstrations to deliver quick wins that teams can use to engage and nurture acceptance among colleagues, funders, and governments.

Ability

Ability refers to the variety of factors that enable a team (and other stakeholders) to create change. In this context, it is useful to distinguish between capabilities (individual and organizational), time and resources. This section provides a general overview of abilities for change across the Demonstrations.

Capabilities: The Demonstrations have all had an explicit focus on helping to build new system capabilities in UNDP country offices. Our M&E data suggests that these efforts have been relatively successful. Capabilities refer to a suite of skills and deeper shifts in mindsets, including systems thinking, abstraction, and being comfortable with ambiguity and uncertainty. For instance, in a recent survey asking Deep Demonstration teams about the most significant changes they’ve been experiencing as a result of the Demonstrations, 57% of respondents expressed an improved ability to see and analyze problems in a more holistic way while 30% of respondents said that the Deep Demonstration is breaking down silos and improves collaboration across teams in the office. These achievements help lay the foundation for change in the office and beyond.

Despite improvements in individual capabilities, country offices are at times constrained by existing organizational procedures and incentive structures. For instance, current financial systems and M&E procedures in UNDP sometimes constrain offices as they seek to design, finance, and manage new portfolios based on emergence and adaptation.

Time: Across country offices, time constraints have limited Demonstrations’ ability to create change. Learning to understand and engage with complex systemic challenges is hard and time-consuming work. Investing the requisite time to do this work has been a big challenge for teams and leadership — not least during the COVID-19 pandemic (though lockdowns have also freed up staff as they haven’t been able to undertake work related travel). This has limited teams’ ability to acquire new capabilities and drive change in the office. A Resident Representative (head of a UNDP country office) explained this challenge: I feel I am constantly in the line of fire of my team given the workload and competing tasks… some of the staff might still perceive the deep demo effort as an additional task as opposed to embracing it as a new way of doing things. In this context, we (the SIU) need to better support and tailor workflows to the conditions that teams are facing.

Resources: UNDP’s innovation facility has provided financial and technical support to the Deep Demonstrations. But the first generation of Deep Demonstrations are now moving into a phase where they seek to activate portfolios of interventions intended to tackle complex challenges. Activating (implementing) a portfolio requires additional resources beyond what the Innovation Facility can provide. Finding these resources is challenging in a context where many country offices face compounding crises and multiple demands, and where donors are cutting aid budgets. Yet, some offices are gaining traction, leveraging the Deep Demonstrations to engage and build support (acceptance and resources) from funders such as Sweden, Finland, and philanthropic foundations.

Taken as a whole, improvements in capabilities and the availability of resources have enabled the Deep Demonstrations to drive change. Yet, the room for change has also been restricted by factors such as time constraints, competing demands, and certain organizational procedures. Tackling these constraints are important focus areas for the SIU moving forward.

Lessons learned about building ability: For the SIU, lessons learned about how to help Country Offices to build abilities for driving change include:

- Devote greater attention to tackling some of the structural bureaucratic constraints to change. This entails working with operations, procurement, and other colleagues in UNDP to reform the processes and systems that country offices (are required to) use when they design and implement initiatives.

- As colleagues return to the office and can travel, they will have less time to participate in long online Deep Demonstration workshops. We therefore need to adapt the formats and level of effort required from country office teams in future Demonstrations.

- As noted above, we are planning to help offices ensure that future Demonstrations engage with funders at a much earlier stage not only to improve acceptance, but also to support our financial ability to drive change.

We are painfully aware that transformational change does not happen in a one-year period, and that it is not caused by one single actor. Change is often slow, incremental, and it is influenced by a variety of factors. The Deep Demonstrations are no exception to this. Yet, we find it useful to try to understand the space for change and what is shaping it. Looking at the authorization, acceptance and ability for change is a helpful heuristic for doing this.

As we roll out a new generation of Deep Demonstrations, we will continue to refine our understanding of how we are supporting change and where we can improve. If you have done similar work or if you have suggestions for how we can improve our understanding of the drivers of change, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

![]() Click for all resources related to SDG Integration. Go back to the CoP SDG Integration dashboard.

Click for all resources related to SDG Integration. Go back to the CoP SDG Integration dashboard.

Please log in or sign up to comment.